What Your Data Discloses About Others

Is Europe getting a hold on tech? New legislation such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Services Act, and the Digital Markets Act have followed each other in rapid succession, and the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act is in the pipeline. Internationally, Brussels is hailed as setting a high global standard that ripples through the world, with different countries adopting the European blueprint (Bendiek and Römer, 2019). Beyond rules on paper, European lawyers are winning major lawsuits. Recently, based on the GDPR, it was ruled that social media giant Meta has to ask in a yes/no question for permission to show personalised advertisements (Milmo, 2023; noyb, 2023). While a major win for digital autonomy advocates, that ruling also exemplifies the focus on individual choice in reining in the fourth industrial revolution. Yet, there is another dimension to this story, one that is at the heart of the profitability of Big Tech yet remains inconspicuous to the public eye – the impact on others of sharing one’s data

It is not just about you

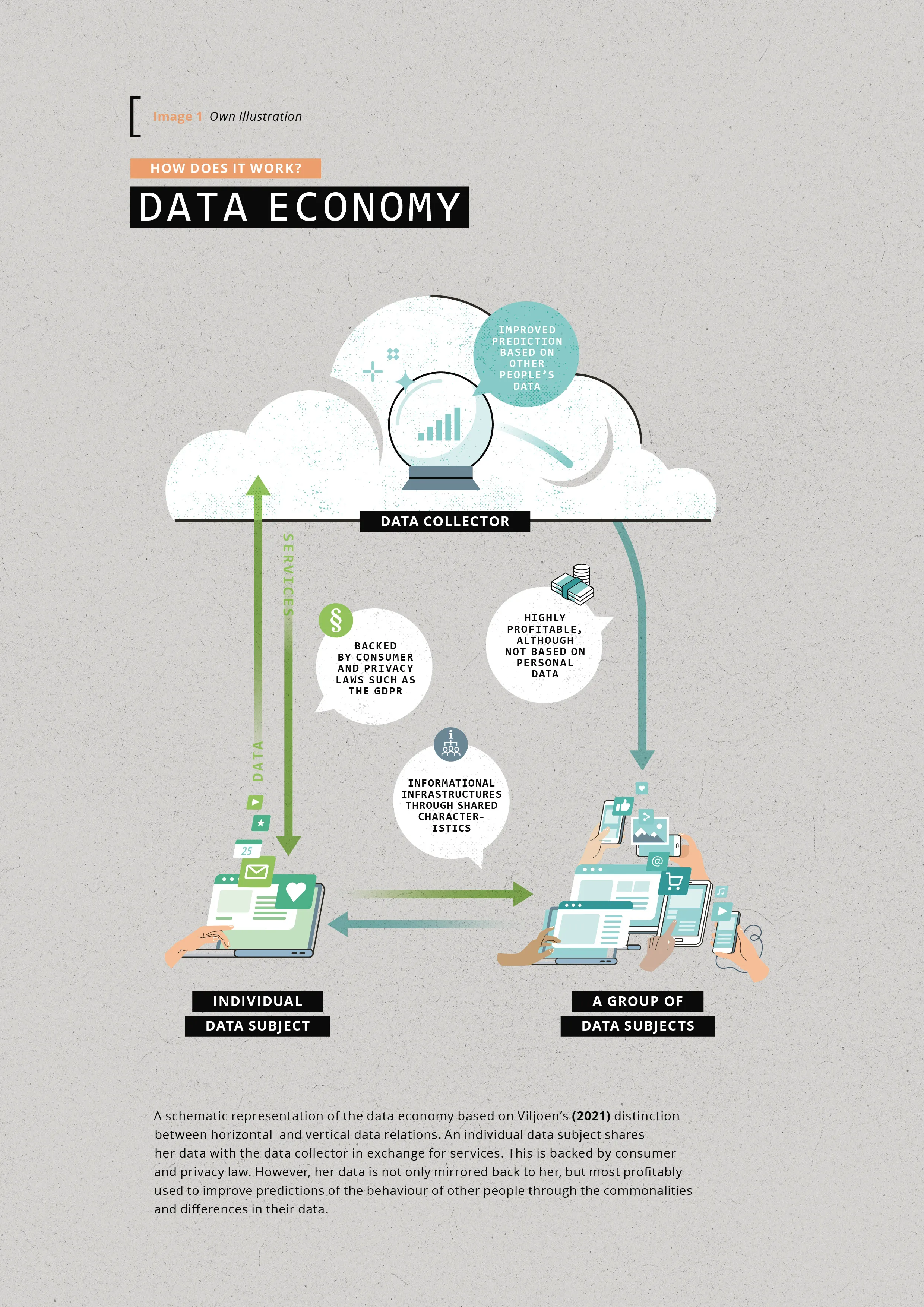

Current data regulation (the laws regulating how data can be extracted, stored, and shared by, for instance, companies) needs to be revised (Micheli et al., 2020; Pike, 2020), as current buzzwords such as transparency, consent, and personal data protection distract from the real deal (Affeldt and Krüger, 2020; Bietti, 2020; Finck and Pallas, 2020; Graef et al., 2018; Søe et al., 2021). In her recent publication ‹Relational Theory of Data› (2021), US law scholar Salomé Viljoen calls attention to the social meaning of our data and the value it holds for data collectors such as Meta, Alphabet, and Amazon. Viljoen, who specialises in the political economy of social data, proposes an informational framework that distinguishes a horizontal and a vertical dimension (2021, p. 607). The vertical dimension delineates the connection between the data subject and data collector [Image 1]. It captures the technical aspect of how data flows as well as legal considerations of the contract under which the data extraction takes place (‹terms and conditions›). This relation plays a key role in current regulation: Is privacy breached? Is there genuine consent? But also, how could individuals financially profit from the value of their data? Then there is the horizontal dimension, which looks at the links between different data subjects [Image 1]. The data collectors connect individuals’ data and use the patterns that emerge to predict behaviour for an even bigger group. This informational infrastructure is at the heart of the digital economy today because it can express social meaning through data (Viljoen, 2021, p. 607). Take for instance AI that helps smooth job application processes. The idea is simple: based on parameters important to the company, AI will filter out job applicants. However, often such AI is based on the profile of current successful (white male) employees (Dastin, 2018; Drage and Mackereth, 2022). This information is used to train the algorithm to find the best prospective candidate.

///<quote>

In the upcoming

European AI Act algorithms

used during recruitment

are flagged as high risk.

///</quote>

As such, data about one group of people is extrapolated to determine whether new applicants will be successful in their future jobs. Hence, the significance of the employees’ data lies not in what it tells about them but instead in what it can predict about others. Let’s imagine Alex, Bo, and Charlie. Alex is a successful employee at the company to which Bo and Charlie are applying. This company uses AI to filter through its many applications and selects Bo as a potential candidate but not Charlie, even though Charlie and Bo have very similar credentials – the only difference is their gender. Like the infamous Amazon hiring algorithm (Dastin, 2018), the AI determined that CVs with gendered words such as ‹women’s college› or ‹women’s chess club› indicated a smaller likeliness to fit the company because the CVs of successful employees, such as Alex, did not contain such words. Societal concerns about biased programmes are being voiced and are starting to be picked up in legislation. In the upcoming European AI Act, for example, algorithms used during recruitment are flagged as high risk (Joyner, 2023). Still, these regulations are yet to address fully the relation dynamic of the data’s value.

Colouring someone else’s image

It is important to emphasise that the population-based connections are a problem not because they are incidental to the way our data economy works. Rather, they are an issue because, even though they are the crux of the data economy (Viljoen, 2021, pp. 586–589), they stay out of the limelight. For instance, a recent study for the European Parliament finds that the money Amazon makes from selling data about the people who browse its website does not stem from personal data at all. Instead, it uses anonymised data to create abstract profiles describing groups of people (Mildebrath, 2022). The Cambridge Analytica scandal is a notorious example of how the data of a few is used to predict and steer the behaviour of many others. The political consulting firm used social media data to create psychological profiles (Illing, 2017). Using those profiles, it targeted particular groups with specific election advertisements that were predicted to nudge their political views. By doing so, Cambridge Analytica is said to have influenced several elections (Amer and Noujaim, 2019). The crucial angle Viljoen’s analysis provides is that it shows what mechanisms are at play – and how these remain unregulated. During the 2016 US elections, the data shared by a quarter million people enabled Cambridge Analytica to target 800 times as many users (Viljoen, 2021, p. 605). So, the protection of an individual’s right to consent to data sharing becomes toothless when risks arise not so much for the individual who shares the data but for others.

The new ruling by the European Data Protection Authorities against Meta does add a second step of protection: Instagram and Facebook users now have a right to choose whether they want to be shown personalised ads (Milmo, 2023; noyb, 2023). Although this right is an important improvement, it still overly focuses on the individual. It asserts the worth of choice but does not address the collective and societal harms of, for instance, influenced elections. Collective harms occur when the interests of a group of people are lain aside (as might for instance be the case in AI-aided application processes) whereas societal harms refer to societal interests, such as equality, democracy, or the rule of law (Smuha, 2021). Often, we only become aware of injustices when they reach the court. In Finland, for example, a bank was fined for denying a man a loan based on his similarity to the creditworthiness of others due to his mother tongue and the neighbourhood in which he lived (Orwat, 2020, pp. 38–39). In Pennsylvania, an algorithm determined the risk of child abuse based on a data set of families who use public services. And although the social workers handling this algorithm acknowledged its limitations, they let it overrule their own expertise (Eubanks, 2017).

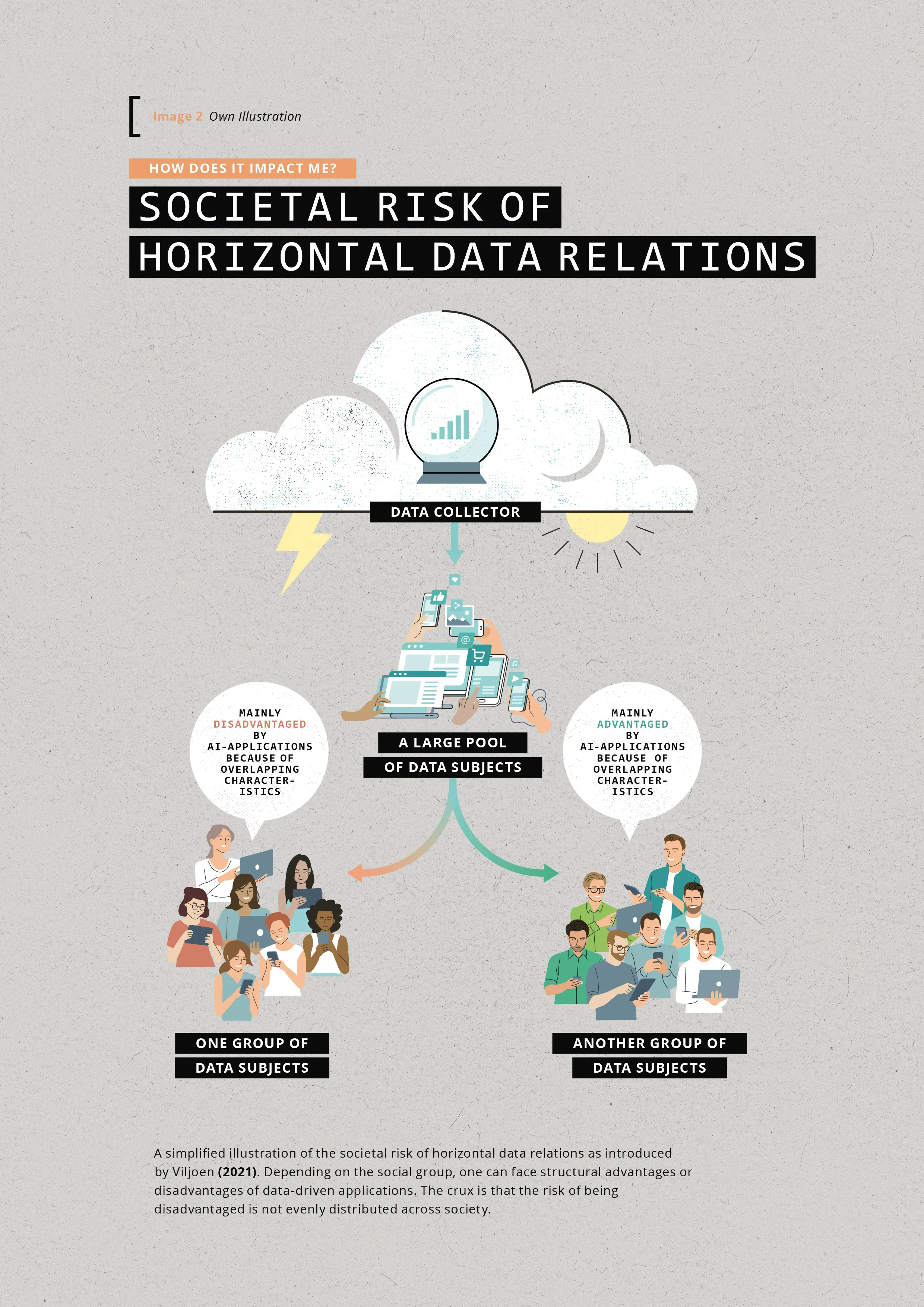

Applied ethics

Current data regulations such as the GDPR focus primarily on the link between the data source and data processor, with a heavy emphasis on personal data and personal choice. However, this emphasis does not capture the impact one person’s data might have on someone else. So, beyond privacy and surveillance concerns, there is a more fundamentally social dilemma when we decide to share our data: we do not know in what way our data is used to make predictions that could disadvantage other people. Socially more advantaged groups can agree to share data that will unknowingly benefit them but put other people at risk (Viljoen, 2021, pp. 613–615). We run the risk of overlooking or misconceiving injustices that arise on a collective or societal level, especially since the spread of the risks and benefits of AI applications across society is uneven: if you have the ‹better› mother tongue, live in a well-off neighbourhood, and never rely on public services, you would, for instance, not run into the same problems when applying for a loan or are less likely to be flagged as a member of a family where child abuse may occur. Such characteristics do not randomly influence the outcome of a computation but will consistently affect the same groups in society. What this persistent differentiation shows us is that, over time, when data-driven applications become more and more entrenched in our society, different groups of people with different characteristics (such as gender, race, or wealth) will have fundamentally distinct experiences with AI.

///<quote>

It is the tech that

facilitates a further

divide in society.

///</quote>

Researcher Frank Pasquale (2018), for instance, has found that wealthy people face less privacy breaches than poor people, whereas it is people of colour who are structurally set back by AI in health care or the judicial system (Obermeyer et al., 2019; Green, 2020). Thus, with some groups enjoying the benefits and others facing recurring increased risks, these applications will affect the social fabric of our societies in the sense that it is the tech that facilitates a further divide in society [image 2]. People’s lived experience with these data-driven applications will become so unalike that it might become more difficult to find common ground for ethical regulation.

Think for instance about the question of how to make digital systems trustworthy for everyone. If you assume some societal groups experience huge advantages, then obviously there is reason for them to trust these machines and the regulations that govern them. But you must then also assume that other groups have good reason to distrust such AI: those which, non-coincidentally, have less access to the public debate and less influence on policy-making and which are the ones most held back by such innovations. So, to acknowledge the differentiated risks societal groups are facing and to ensure technological developments constitute progress for everyone, regulation must focus less on individual rights and more on the social implications of data.

Next page