Open Source Hardware and Open Design

Enablers of a Sustainable Circular Economy

The circular economy is on the rise. This conclusion is permissible in light of the EU Commission’s actions, which put ideas of a circular economy prominently into the European Green Deal and thus direct our attention to extracting and reusing resources. The goal is to keep those resources in the system. This goal is relevant for sustainability since the environment is harmed by extracting new resources and disposing of products.

///<quote>

Refuse; rethink; reuse;

repair; refurbish;

remanufacture; repurpose;

recycle.

///</quote>

It is also of strategic interest for security of supply, not just in times of crisis. But the question is how do we get there? How do we have to change our way of producing, of doing business, of living so that true cycles can emerge?

Before we get into this, let’s take a brief look at the circular economy debate. It presents itself primarily as a discussion of actions. Verbs such as ‹refuse›, ‹rethink›, ‹reuse›, ‹repair›, ‹refurbish›, ‹remanufacture›, ‹repurpose›, and ‹recycle› are the focus of attention (Kirchherr et al. 2017).

We might imagine, for example, that we travel less and therefore don’t need a suitcase (refuse); we conduct our meetings online instead of on-site (rethink); If we travel, we don’t buy a new suitcase, we buy one second-hand (reuse). Or maybe we replace a broken wheel (repair) before we start our journey, or we take an old suitcase with just a handle and upgrade it by adding wheels (refurbish). Maybe we buy a suitcase from a company that does just that, refurbishing, on a large scale (remanufacture). And when we no longer travel but settle in, we don’t throw the suitcase away but use its shell as drawers in a cabinet (repurpose). And we make sure that the suitcase is made of materials that can be recovered cheaply and without loss of quality (recycling). The more concrete and detailed the discussion about a circular economy becomes, the more unresolved questions on its implementation arise. How must such a repairable suitcase be designed? How is it manufactured? Can the practices also be applied to smartphones? The circular economy presents us with complex problems. It needs new forms of cooperation between the different actors in our economy – for instance, recycling facilities need to know how the products they seek to recycle can be disassembled and which materials they may extract. Or repair shops might need information on the product design to accomplish their task.

Digital technology can play an important role in dealing with some of these issues through implementing new forms of cooperation. It has fundamentally changed the way we work together. The question is which tools from the digital realm are suitable for circularity? A growing number of scientists, hardware developers, and activists (e.g., Bonvoisin, 2017; Undheim, 2022) believe that the methods developed in the cosmos of open source hardware and open design have received far too little attention although they actually seem to be the methods with the most potential.

If we look at the different practices of the circular economy described above, ranging from rethinking to reusing, repairing, and recycling, some questions arise: Who shall perform them? And how? What needs to be in place to make them possible and likely? We argue that these actions need to be supported by:

- The design of a product

e.g., Can the case be opened for repair without damage? - The intellectual property rights with regards to a product

e.g., Can spare parts be produced by everyone or are they design-protected? - Transparency

e.g., Is the information necessary for efficient and effective recycling available? - Infrastructure

e.g., Are facilities and institutions available for recycling or repair? - The mindset of people

e.g., Do people think about repairing or repurposing? - Legislation

e.g., Can recovered materials be used in new buildings?

As yet, few of the areas mentioned are at such a level that they can support circular practices. Repair cafés regularly encounter all these problems. They are initiatives in which volunteers get together with the mission to make broken things work again. A toaster cannot be repaired because you cannot open its casing, no one produces spare parts for it, or the information needed to repair it cannot be found. Establishing a circular economy entails an incredibly complex and intertwined set of problems. Open hardware and open design can help to deal with this.

Openness to reduce complexity

Open source hardware and open design are methods that have emerged in the digital age. Both have the goal of involving more people in designing and producing physical objects.

///<quote>

With open technologies, the

normally vertical production system

focused on individual companies

or groups of companies

will be opened up

and aligned horizontally.

///</quote>

The core of open source is therefore ‹cooperation›. Open source hardware focuses on sharing blueprints for products that anyone can use commercially for any purpose. «Open source hardware is hardware whose design is made publicly available so that anyone can study, modify, distribute, make,

and sell the design or hardware based on that design».1

1Open hardware definition, by Open Source Hardware Association: https://www.oshwa.org/definition/ (visited: 23.03.2023)

At its core, open hardware is a publicly available and freely licensed documentation that allows reuse. The documentation contains all the important information about a specific item needed for reproduction.

Open design focuses on the question of how to design products to make collaboration as easy as possible. There is an emphasis on design that is simple and easy to understand and that can be manufactured with widely available tools and parts. In the definition of open source hardware, this emphasis sounds like this: «Ideally, open source hardware uses readily available components and materials, standard processes, open infrastructure, unrestricted content, and open-source design tools to maximise the ability of individuals to make and use hardware». Open design thus facilitates collaboration through the construction and design of an object, which also includes a modular structure that simplifies the detachment of components. If we follow these suggestions, the pool of people that can work with a product increases. Ensuring more people can work with products will include circularity practices: Available documentation and the use of standard parts make repair, repurposing, remanufacturing, and even recycling easier and therefore more likely. A toaster that follows the guidelines of open source hardware and open design does not pose a challenge to any repair café. Maybe it doesn’t even need a repair café because you can simply repair it yourself right at home. For example, with open hardware it may be possible to replicate spare parts easily and independently of the manufacturer when they are needed. Studies show that the probability of repair increases when the spare part is quickly available. A 3D printer that can be found directly at the repair location, combined with freely available CAD drawings, therefore increases this probability (Chekurov & Salmi 2017).

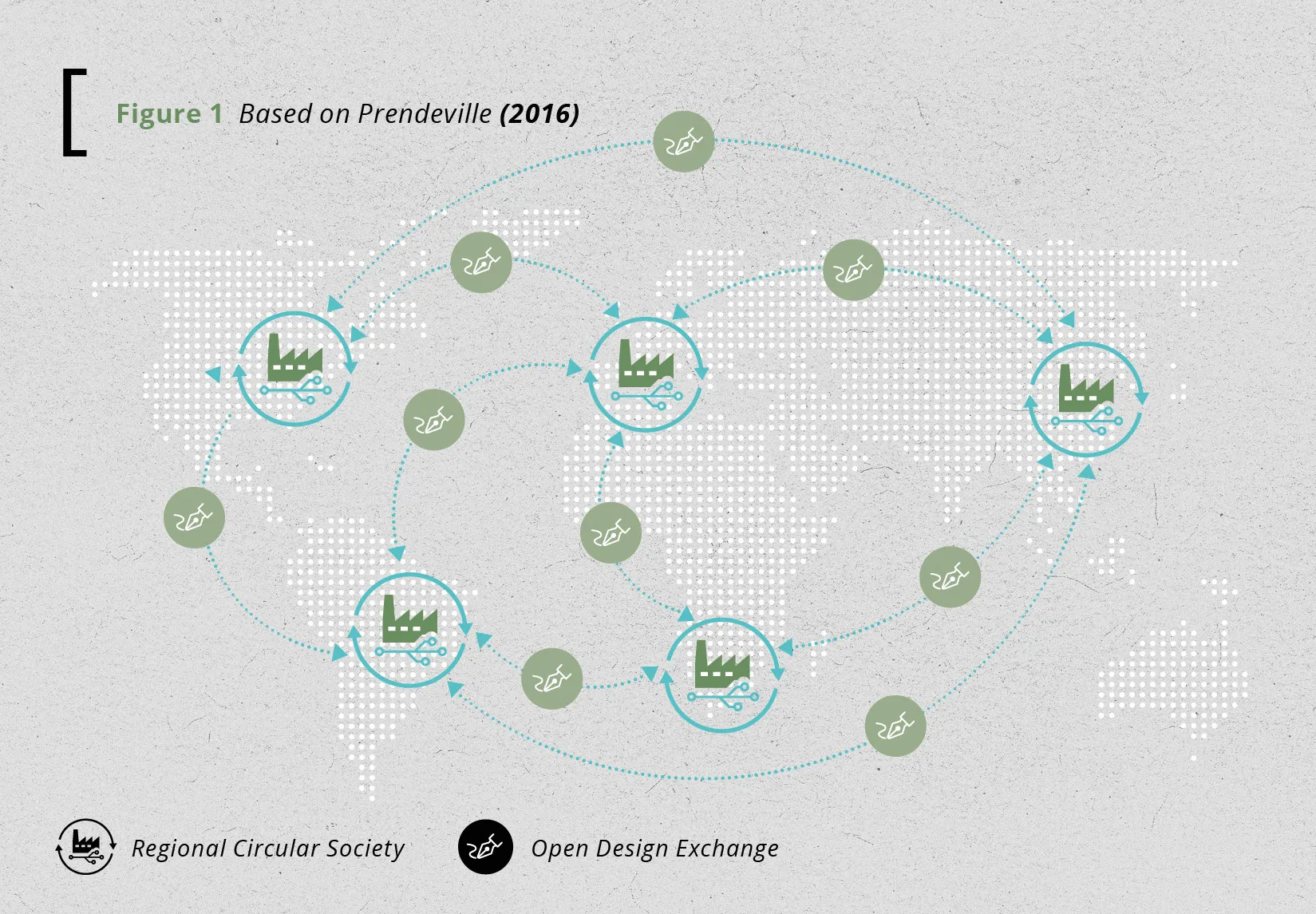

But it’s not just about repair, it’s also about local production. Open digital designs that can be easily shared over the internet enable a global innovation and production system focused on local opportunities. The maker movement’s saying, ‹design global, manufacture local›, gets to the heart of this [Figure 1]. With open technologies, the normally vertical production system focused on individual companies or groups of companies will be opened up and aligned horizontally. Horizontal means that anyone can become part of these networks, including companies, research institutions, or civil society actors. Open networks will be created that can easily cooperate with each other through freely available information and without knowing each other.

Building this kind of circular economy is challenging. We – the open hardware community – were accused of making the approach even more complex with our proposal of an ‹open-source-enabled circular economy›. In this article, we argue that the opposite is the case. We believe that open source is the only way to deal with the existing complexity. Break it down and make it manageable. Supporting and promoting open source is therefore an inevitable part of any initiative – whether from business, politics, or civil society – that really wants to make a circular economy happen, to build a circular society in which everyone can participate.

To implement this economy, design specifications are needed in addition to information (e.g., digital product passports). The current EU draft for revising the ecodesign requirements already contains important aspects, such as the specification of modular construction or the possibility of ‹upgrading›.2

2Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for setting ecodesign requirements for sustainable products and repealing Directive 2009/ 125/EC https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELE%3A52022 PC0142

However, the decisive factor is how these aspects will be implemented and applied to product areas. To design openly, we need concrete specifications, and we must be provided with design files. In addition to design specifications, however, what are needed are incentives and support for those who are testing new business models geared to open technologies. Numerous people have already set out on this path and are leading by example. Supporting them should become the focus. These actors are among the most innovative of our time if innovation means designing things to be participatory, fixable, and changeable.

About the authors

- Lars Zimmermann is a designer, activist and teaches at universities. He runs the design studio Mifactori and conducts research on sustainable modular open source furniture in the project ‹Trikka›.

- Maximilian Voigt works for the Open Knowledge Foundation Germany on open hardware. He focuses on the potential of open technologies and infrastructures for the circular society. Maximilian studied engineering, journalism and philosophy of technology and is a board member of the Association of Open Workshops – the German umbrella organisation of makerspaces.

References

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M.P. (2017). Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. SSRN Electronic Journal. 127. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-9R-Framework-Source-Adapted-from-Potting-et-al-2017-p5_fig1_320074659

- Bonvoisin, J. (2017). Limits of ecodesign: the case for open source product development. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering. 10 (4–5): 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2017.1317875

- Undheim, T.A. (2022, April 4). Why We Need Open Manufacturing And What That Would Mean For You. Forbes. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/trondarneundheim/2022/04/04/why-we-need-openmanufacturing-and-what-that-would-mean-for-you/?sh=76e1bb962512

- Chekurov, S. & Salmi, M. (2017). Additive Manufacturing in Offsite Repair of Consumer Electronics. Physics Procedia 89: 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2017.08.009

- Prendeville, S., Hartung, G., Purvis, E., Brass, C. & Hall, A. (2016). Makespaces: From Redistributed Manufacturing to a Circular Economy. Sustainable Design and Manufacturing. 2016/ 52. 577–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32098-4_49